Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

Qui and Phong on the road north of Hanoi, Vietnam

Vietnam is losing its children.

The numbers tell only part of the story of human trafficking, and those numbers vary depending on who you ask. Vietnam claims nearly five-thousand girls and young women have been forced into a life of slavery in neighboring states since 2004. But independent groups believe the number is much, much higher. Hagar International cites a figure of 400,000 missing since 1990.

Vietnam is losing its children

For years, girls and young women have been taken -- kidnapped and trafficked across the border into Cambodia and southern China. Trafficking experts have connected this underground trade in China to the country's one child policy, which traditionally favors boys.

US Ambassador, Luis CdeBaca, charged with fighting human trafficking worldwide, told me the results manifest in various ways: "I think that we've certainly seen in some of the countries, which have a very skewed male-female ratio, that a market has sprung up now with what's in effect servile marriage--women who are brought into these situations are being used more as slaves than as wives." Others have been targeted specifically for prostitution.

Many young women disappear into big cities. Some give birth, their babies held by traffickers as insurance that these enslaved girls and women won't run away. A tiny number find freedom when they escape or are rescued. And that's what this story is all about.

Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

On The Road Heading North

On The Road Heading North

It's mid-morning. A light rain is falling over Hanoi. The car I'm in weaves through chaotic traffic. Sitting in front and to my left are two teenage girls. Laughter fills the car. I'll call the girls "Qui," and "Phong." One is 17 and the other is 19. They're all smiles, but don't let their laughter deceive you. In the last 12 months, Qui and Phong were kidnapped, severely beaten, raped and sold into slavery by organized human trafficking rings.

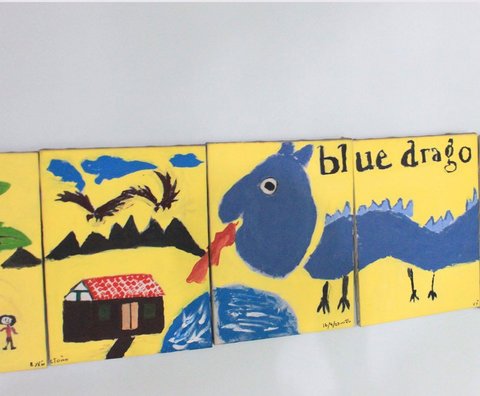

The girls found their freedom with the help of the hero sitting next to me. He's Ta Ngoc Van -- who prefers to be called Van Ta -- a graduate of Brandeis University's Heller School and a lawyer for the Hanoi-based anti-trafficking organization, Blue Dragon. Van Ta describes how he rescued Qui.

Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

Ta Ngoc Van, a lawyer for the anti-trafficking organization, Blue Dragon.

"She was locked up in Guangdong Province in China, and one night I come back from my commencement in the U.S. and the police, the Chinese police, rang me and asked for my help to rescue this girl," he said.

The three of us and the driver are heading north out of the city to Qui's village. She's being reunited with her family. It's hard to hear above the din of the noise in the car, but Van Ta says on the first night of her kidnapping, there were 47 men. Forty-Seven men.

Qui is nearly 18, and was 16 when she met a man while visiting Hanoi. They met in an Internet café, and she was smitten. They dated for six months, and the man, six years her senior, said he loved her. But when they arrived at the border, he handed her over to sex traffickers in an exchange that Van Ta said has been repeated time and time and time again.

On the first night of her kidnapping, there were 47 men. Forty-Seven men.

We've been on the road now for three hours, and the lanes have gotten narrower.

We're traveling the same route taken by some human traffickers heading to China. In a short while we'll arrive at the Muong ethnic village where Qui was born and raised. She suddenly grows quiet and stares out the window toward the rice fields where farmers in blue khakis bend over in ritualistic toil.

Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

Qui is heading back to the poverty she had longed to escape, Van Ta says. We stop before we get to Qui's village because we've been warned that Western visitors here are rare these days. There is concern that my presence will stir unwanted attention.

Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

A foreigner carrying a microphone is even more problematic, so we're going to carry out the interview at a quick stop along the road.

The twenty-three-year-old man whom she fell in love with invited Qui to meet his parents. She turned him down many times, she tells me. But one day, she accepted his invitation and drove many miles past her own village and along the hilly, forested region that separates Vietnam from China. He took her to a house and said he would be right back. The men who burst through the door moments later spoke Chinese. Qui knew then that she was no longer in Vietnam. They stuffed her into the back of a van and drove for what seemed like forever into China.

Qui was raped repeatedly and beaten constantly. The beatings grew worse when she decided to write down the names of all of the Vietnamese girls in the brothel. "They don't want anyone to know that these girls are Vietnamese," Ta Ngoc Van said.

Qui was raped repeatedly and beaten constantly. The beatings grew worse when she decided to write down the names of all of the Vietnamese girls in the brothel.

Officials with the United Nations Inter-agency Project on Human Trafficking believe that in one town in Guangzhou, China alone, there may be one-thousand brothels (including thinly disguised as massage parlors, karaoke bars, etc.) -- all run by organized gangsters, which requires cooperation between Chinese and Vietnamese traffickers. Six months into her ordeal, Qui escaped with two other girls. A sympathetic policeman telephoned Van Ta, and he and a Vietnamese police officer crossed the border posing as tourists to bring her home.

The girls Qui escaped with were recaptured and sold to other brothels. They have disappeared somewhere in China.

The underground trade also works in reverse. Human traffickers often trick and coerce underage Chinese girls and young women in ethnic minority enclaves near the borders of throughout Southeast Asia, according to the UN and various NGO's.

We're minutes away from Qui's home, and we're now passing by a three-room school.

"She was grade 10 when she was trafficked," Van Ta said. "The first year in high school. She is a little bit nervous now to go home."

We make our way through a thicket of trees, where Qui's mother meets us. Mother and daughter hug, and we all quickly move toward the house lest neighbors notice and question.

Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

Qui's family.

In the one-room house, the mother makes tea and every few minutes touches her daughter's face and smiles. Her joy is easily translated. She has eight children and says other people's daughters have also disappeared from this village. Her own sister was kidnapped many years ago, and she has heard rumors of her sighting in southern China.

The mother fears for the next generation, including for her own grandchildren, whose innocence is reflected in a smile or in their playtime at twilight.

The mother fears for the next generation, including for her own grandchildren, whose innocence is reflected in a smile or in their playtime at twilight.

As the mother speaks, Qui's father appears, ferrying a bike through the trees, and hugs his daughter. In his gratitude to Blue Dragon, the father -- who fought for his country during the Vietnam War -- tries to give Van Ta a large bag of rice and a chicken. It is enough to feed Qui's family for two weeks, and a gift they can ill afford. Van Ta thanks him but refuses.

Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

Qui's father

An hour after arriving in this tribal village several miles from the China border, it's time to leave. Qui and Phong sit on the stairs and share a private moment. Qui has been returned to her family. Phong is looking for a family and says she's found one for now in the organization that rescued them, Blue Dragon.

Credit Phillip Martin / WGBH

Blue Dragon headquarters in Hanoi, Vietnam.

Moments after we take to the road, Van Ta's mobile phone beeps. It's a text message from China. A young, prostituted woman using the cell phone of a sympathetic customer texts the number given to her by a woman who recently escaped the brothel.

"She says 'Please help me,'" Van Ta said. "I said, 'Where are you?' She said, 'I am in China, but I am not sure where it is.' I write, 'I will come to help you, but it takes time, and she said, 'Yes, and please keep in touch,' and I said, 'Don't worry, we will find a way to help you.'"

Within hours, I'll be dropped off in Hanoi, and Van Ta, a modern-day abolitionist, will find his way to the Chinese border to try to rescue yet another victim of this underground trade.

NEXT: The Shame of Human Trafficking

This WGBH series was funded by the International Center for Journalists, the Ford Foundation and the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism at Brandeis University. Additional contextual resources for this story are available at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism's website.